By Fred Swegles

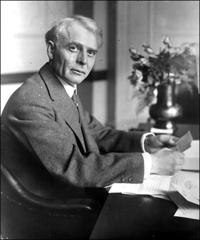

One hundred years ago, Ole Hanson was one of the most famous men in America.

“Fighting Mayor of Seattle,” The Oregonian newspaper described him in February 1919.

“Mayor Defies Bolsheviki in Great Strike,” wrote the San Antonio Evening News.

“How Courageous Mayor Ole Hanson Broke the Big Strike at Seattle,” trumpeted the newspaper in Ardmore, Oklahoma.

“Seattle’s Mayor Saves City from Anarchist Rule,” proclaimed an Indiana headline.

“Seattle Strike Was Attempt at Revolution,” wrote the Santa Ana Register. “Start There, Then Spread to Other Cities, Bolshevists Planned.”

“Hang or Imprison all Reds, Declares Mayor Ole Hanson,” a Kansas newspaper quoted him.

“Bomb Sent to Mayor Hanson of Seattle . . . Attempts Murder of Mayor Hanson,” other newspaper headlines reported.

Hanson, who just six years later would hatch a Southern California real estate venture named San Clemente, achieved folk-hero status in 1919 across America.

The adulation he received as Seattle’s strike-breaking mayor led him to resign six months later to finish writing a book, Americanism vs. Bolshevism. He also is said to have earned more than a half-million dollars (today’s dollars) giving speeches nationwide, calling for a recommitment to Americanism and for roundup and jailing or deportation of subversives.

All this led “Holy Ole,” as some called him, to pursue the 1920 Republican nomination for president. When that fizzled, Hanson resettled in Los Angeles.

He took up real estate in the Slauson Avenue district in Santa Barbara and then, most famously, on a patch of barren beachfront property halfway between L.A. and San Diego.

Seattle’s memories of Mayor Ole Hanson (1874-1940) have resurrected this year with 1919 centennial observations. Then-and-now newspaper articles, magazine pieces, a musical titled Labor Will Feed the People, a republished and updated 1964 book and a University of Washington website commemorate the landmark Seattle General Strike.

There’s also renewed attention to a 1985 rock musical by The Fuse, Seattle 1919.

Ole Hanson, circa 1928. Photos: Courtesy of San Clemente Historical Society

Genesis for a Strike

From multiple accounts, it appears that functions of daily life in Seattle were overwhelmingly unionized 100 years ago. When 25,000 union workers ranging from garbage collectors to restaurant waitresses walked out on Feb. 6 in support of 35,000 shipyard workers already striking over wages, the resulting blanket work stoppage virtually shut down the city.

Fearing violence, Seattle residents had emptied store shelves of necessities. Some armed themselves. Some wealthy people left town. Labor leaders decided which limited functions to exempt from the stoppage. They organized a workforce to feed thousands, keep hospitals running, maintain essentials and ensure public safety.

On the other side, Mayor Hanson deputized a civilian force to assist police, denounced anarchists and urged calm, assuring the citizenry the government would protect life, business and property. He issued this proclamation:

“The time has come for every person in Seattle to show his Americanism. Go about your daily duties without fear. We will see to it that you have food, transportation, water, light, gas and all necessities. The anarchists in this community shall not rule its affairs. All persons violating the laws will be dealt with summarily.”

The Army from Camp Lewis was called in, told to stand by. Hanson refused compromise, set a deadline to end the strike, threatened martial law.

Soon, it became evident the strike wasn’t going to budge shipyard owners or the federal shipping agency to hike wages held down during World War I to assist the war effort. Little by little, sympathy strikers supporting the shipyard workers returned to work. The general strike unraveled.

So why was this peaceful, aborted general strike important? Why did it produce an explosion of headlines nationwide?

Boomtown and Bolsheviks

The World War had ended less than three months earlier. Seattle had been a boomtown, its shipyards winning lucrative government contracts. Workers poured in from all over, spurring a housing shortage, high rents, some unrest, a budding socialist movement.

Shipyard workers, asked to forego wage increases even as the cost of living escalated, expected recompense when peace arrived in November 1918.

Overseas in 1917, a revolution in Russia had ousted the Czar, substituting Vladimir Lenin’s ruthless Bolshevik regime. As newspaper headlines were touting daily in early 1919, insurrections and class warfare were spreading across violence-weary Europe.

Radicals within the Seattle labor movement called upon workers to take over the shipyards.

Anna Louise Strong, described variously in centennial accounts as “a firebrand socialist agitator” and “an early advocate of Communism,” published a call for striking union workers to shut down and reopen industries under labor’s control—“starting on a road that leads ‘NO ONE KNOWS WHERE!’”

That line raised eyebrows—and alarm bells.

Robert Friedheim, in his 1964 book, The Seattle General Strike, wrote that “labor supporters of Russia’s experiment” held large-scale open-air rallies before the general strike that led to riots, declaring that workers “ought to take over, own and run the machines of industry.”

Newspapers, Friedheim wrote, “began to suggest that Seattle might soon face a situation experienced by no other major city in the United States.” He wrote that “newspaper editors began to believe that none of the real substantive issues in the dispute was of sufficient importance to trigger a general strike . . . logically, then, they could only conclude that the strike was the deliberate beginning of an attempt to destroy established society.”

Ole’s Response

Mayor Hanson, elected in March 1918 with a history of supporting workers’ causes, raised the minimum wage of city employees early in his term. As the general strike took shape, he seized upon public fears, denouncing the attempt to shut down Seattle as an unfolding revolution.

The Seattle Times, in a 2019 retrospective, says it wasn’t. “Some local union leaders clearly were inspired by the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution and would have been happy to hasten a collectivist society,” The Times wrote. “But most local labor leaders, part of the American Federation of Labor umbrella, were not revolutionaries, and the strike was not called to foment revolution.”

Hanson claimed that sympathy strikers were being duped by Seattle’s extreme radicals, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), known as “Wobblies,” intent on bringing down America’s form of government.

The mayor sent “several bombastic telegrams” to the New York Times during the Feb. 6-11 general strike, spreading alarm, researcher Trevor Williams recalled in a 1999 essay titled “Ole Hanson’s Fifteen Minutes of Fame.” Overnight, Ole became a media darling.

“He seemed to be the manly leader America needed to pull it out of its postwar mess,” Williams wrote. “Newspapers liked him.”

“He refused to be bluffed by Bolsheviki or intimidated by threats,” the Washington Post wrote as the general strike was imploding. “He had the judgment to discriminate between a labor dispute and a revolution. If every American will stand as firmly for law and order, the attempts of Bolshevism to get a foothold in America will fail utterly.”

Was He a Hero?

Williams suggests that America needed a hero, and Ole “was handy and loud and he looked just like one, if you didn’t scrutinize him too closely. He made a good story . . . it was easier for the writers and the readers to write and read about one man’s fight against anarchists than to try to dissect the complexities of a labor dispute on the other side of the country.”

Ole, in his 1920 book, Americanism vs. Bolshevism, relates how Wobblie-inspired radicals committed acts of sabotage and spread anti-government propaganda during the war. He tells how he clashed with Wobblies from the time he was elected mayor in 1918, right up to and during the strike. Citing other IWW activities elsewhere, Ole wrote, “There was a widespread conspiracy throughout the Union to establish Bolshevism.”

The Seattle strike helped inspire workers to launch a wave of 1919 strikes in other cities. America experienced a Red Scare. Dozens of mail bombs were sent to prominent public figures to coincide with May 1, International Workers Day. No one died, but a message was sent.

One package arrived at Mayor Hanson’s office while he was away. “Fortunately, Hanson’s clerk, who opened the parcel, held it the wrong way up,” Time magazine reported, “and the bomb failed to detonate.”

By the 1920 Republican National Convention, America had grown tired of Ole’s oft-repeated rants. Warren G. Harding was nominated for president and won.

“Less than a year later, he was hailed for breaking the Seattle strike, and Ole Hanson was looked on as more of a crank than a hero,” Trevor Williams wrote. “His 15 minutes were long gone.”

Legacy of Ole

Mayor Hanson was a convincing orator, historian James Gregory wrote. “A political associate of Hanson’s said years later, ‘He just seemed to be wound up tight. I never heard anything like old Ole until Hitler came along,’ ” Gregory wrote. “‘He’d get so worked up, he’d almost be screaming. He sure sounded sincere.’”

A century later, it’s clear that Communism was an overpowering, enduring 20th-century fear that America survived.

Six years after his stint as mayor, Ole would switch gears, mellowing his oratory into flowery descriptions of the idyllic Spanish Village by the Sea he planned to create for lot purchasers at San Clemente.

“I vision a place where people can live together more pleasantly than in any other place in America,” Ole wrote. “This will be a place where a man can breathe! I have a clean canvas, and I am determined to paint a clean picture.”

It sounded remarkably like heavenly sales pitches he had written for his first waterfront hamlet, Lake Forest Park, which he founded north of Seattle before his election as mayor. Ole’s San Clemente sales tent opened on Dec. 6, 1925, enormously successful from the outset.

Ole remains an icon of San Clemente. In 1976, the city council proclaimed Dec. 6 to forever be Ole Hanson Day.

Learn More

For a retrospective of 1919 Seattle, read Friedheim’s The Seattle General Strike, Centennial Edition. For a lively firsthand look into Ole’s 1919 mindset, read Americanism vs. Bolshevism, with Ole’s personal account of the strike, the evolution of Bolshevism and his prescription for America, confronting the issues of his time.

“We must cooperate and conquer ignorance, poverty and injustice,” he wrote. “We must build on the foundations laid down by our ancestral fathers. Our great experiment in government must not be allowed to fail.”

Fred Swegles is a longtime San Clemente resident with nearly five decades of reporting experience in the city. Fred can be reached at fswegles@picketfencemedia.com.