Fred Swegles

By Fred Swegles

“I could’ve been a millionaire if I’d wanted to,” Harry Comber once said.

He was San Clemente’s first motorcycle cop, hired in 1929. Two years later, he was appointed the third chief of police in San Clemente history.

He made San Clemente famous, writing notorious numbers of speeding tickets along old Highway 101 in San Clemente.

Meanwhile, patrolling the streets and coastline of San Clemente, he busted bootleggers trying to sneak illicit liquor through San Clemente during Prohibition.

“Every cop in the country was on the take in those days,” Comber would tell me decades later during the final chapter of his life.

He resisted the bribe attempts, he proudly declared.

As we related in the San Clemente Times on Oct. 8, Comber became embroiled in a political controversy over his traffic tickets, which local merchants complained were sullying San Clemente’s reputation and driving away business. He resigned in 1933 to “preserve harmony,” he said.

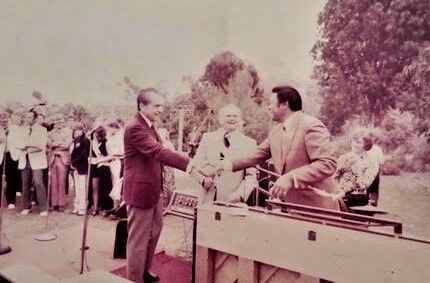

Comber went on to a successful law enforcement career in Los Angeles. He happily returned to visit San Clemente in the 1970s to share recollections—his liveliest stories being about bootleggers trying to sneak illegal whiskey up and down the coast.

Harry Comber was named police chief in this issue of El Heraldo de San Clemente. Newspaper clipping: Courtesy of S.C. Historical Society

RUM RUNNERS

“Instead of collecting millions,” I wrote in a Daily Sun-Post profile, “Comber says he collected adventures. Time and again, he got shot at, got offered bribes, and arrested bootleggers who couldn’t believe he wasn’t on the take.”

In one case, Comber claimed to have captured 14 smugglers on the beach in San Clemente with a stash of liquor, turning down a $5,000 bribe to return the contraband.

If you convert that online into 2020 dollars, $5,000 in 1930 would translate to about $78,000 today.

Another time, Comber said, he turned down an ongoing offer of $3,750 per week to turn his eye from contraband.

All he had to do, he said, was just “stay away.”

HOW IT WORKED

Clandestine shipments often would arrive by sea in speedboats. Shipments might land at Cotton’s Point, Calafia Beach or the San Clemente Pier, local historian Doris Walker wrote in her book The Heritage of San Clemente.

“Large ocean-going Canadian warehouse ships filled with cartons of fine vat-cured whiskeys and West Indies rum, among other tempting types, anchored legally in international waters three miles or more offshore,” Walker wrote.

“Many fishermen along the isolated Orange County coast were recruited to serve as rumrunners, shuttling the bottled goods from ship to shore,” Walker wrote. “It became an honorable as well as lucrative profession, especially coming as it did at the start of what would develop into The Great Depression. The rummies were even admired for the danger they faced and the coveted goods they delivered.”

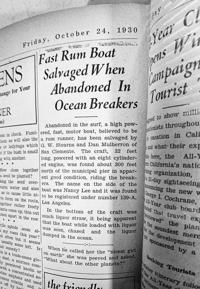

El Heraldo de San Clementedescribed one high-powered motorboat recovered 300 feet north of the pier, abandoned in the surf line, evidently having been “seen, chased and the liquor dumped in the ocean.”

Other bootleggers smuggled the goods by car, up or down Highway 101.

Former San Clemente Police Chief Harry Comber is pictured with his badge collection, after retirement, in a clipping of a 1970s profile written by Fred Swegles.

INTRIGUE IN SAN CLEMENTE

In 1931, El Heraldo reported a seizure of 75 cases of liquor by federal officers from three cars at San Clemente—one of the biggest busts in the town’s history.

Another article told how Chief of Police Comber and Officer Earle Coleman pulled over a suspiciously slow-moving car, finding 15 gallons of “moon” in the back seat.

“Well, boss, I guess you all got me,” the suspect was quoted as saying. “And it was good stuff.”

Comber said he once halted a gasoline tanker truck, its tanks full of contraband booze.

He said he refused bootleggers’ offers, “very much satisfied” with his job as police chief.

“San Clemente paid a better salary than any other city,” he told me.

HAPPIEST PLACE ON EARTH?

So, what did Comber do with the bootleg liquor he seized? To hear him describe it, evidently The Great Depression in San Clemente wasn’t quite as depressing as it could have been.

“I used to give liquor to the citizens,” Comber said. “I’d say, ‘Take it out and destroy it for me!’ ”

He insisted he only gave it to citizens he was confident wouldn’t sell it.

“Everybody knew everybody,” he said. “We were one big family. It was a wonderful game in those days.”

And maybe, by some stretch of the imagination, Comber could rationalize his giveaways. Prohibition, which lasted from 1920 through 1933, merely outlawed the manufacture, transportation and sale of booze—not drinking it.

“By law, any wine, beer or spirits Americans had stashed away in January 1920 were theirs to keep and enjoy in the privacy of their homes,” history.com reported. “For most, this amounted to only a few bottles, but some affluent drinkers built cavernous wine cellars and even bought out whole liquor store inventories to ensure they had healthy stockpiles of legal hooch.”

A 1931 issue of El Heraldo de San Clemente describes a bootlegging seizure, next to stories about the city council wanting to donate 20 acres for a high school site, Ole Hanson being named chairman of a countywide hotel promotion association, three Spanish Village residents being injured in a crash, and more. Newspaper clipping: Courtesy of S.C. Historical Society

NO HARD FEELINGS

Comber held no grudges over the political spat he said had cost him his job. During his senior years, he told only happy memories of San Clemente.

He insisted back in 1933 that he had issued a slew of speeding tickets along Highway 101 on instructions of the city council.

ORIGINS IN S.C.

Hailed for his “honesty, integrity and efficiency” when named police chief, Comber said he originally got the job of San Clemente traffic cop because he’d been a motorcycle officer in Seattle, where San Clemente founder Ole Hanson had been mayor.

Comber said the first speeder he ticketed in San Clemente turned out to be a city councilmember and, instead of reprimand or dismissal, he got a commendation.

Earlier, in Seattle, his first assignment as a traffic cop was just as memorable. He said his motorcycle, pursuing a speeder, slipped on a slick of cow manure and crashed.

Fred Swegles is a longtime San Clemente resident with five decades of reporting experience in the city. Fred can be reached at fswegles@picketfencemedia.com.