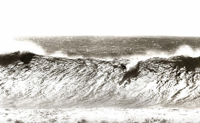

How the famous ‘Swell of ’69’ played out, and why any surf is a good thing these days

By Jake Howard

In December of 1969, Dana Point’s Art Brewer found himself on the North Shore of Oahu on assignment for Surfer Magazine. Making $500 a month, in ’69, he stepped in to replace Senior Photographer Ron Stoner and was sent directly on his first-ever field assignment.

“There were only a couple other people shooting. The North Shore was a completely different world back then—very quiet, very off the beaten path. I was going to be there for four months,” Brewer recalled.

Like so many things in his early career, the timing couldn’t have been better for Brewer. After only days on the ground, the Pacific Ocean roared. On Dec. 4, the mother of all swells hit. Waimea Bay was so big that the waves closed out the entire bay. The Kam Highway flooded. Sixty homes were destroyed, and for 72 hours, it was pure chaos.

“It was dark when the swell really hit, and we could hear the emergency sirens and public address warnings,” Brewer said. “We were evacuated to the field where Sunset Elementary School is today. It was a long couple of days.”

The swell was actually a confluence of a couple of storm systems in the Pacific that created a storm front stretching from the Gulf of Alaska to Hawaii—a distance of more than 2,000 miles. It was later surmised that the winter of 1969-70 was experiencing a weak El Niño effect, which warms the Pacific’s water temps, in turn fueling larger-than-average storms and swells.

The action kicked into overdrive around Dec. 1-2, 1969, when the swell hit Kauai first, delivering 30-foot surf before pushing on to Oahu. With the surf too big for any of the North Shore reefs, a handful of surfers found their way to Makaha on the west side of the island.

Sheltered by Ka’ena Point, the surf was still huge, but considerably more manageable. Among those tempting fate at Makaha were George Downing, Buzzy Trent, Charlie Galanto, Bobby Cloutier and one Greg “Da Bull” Noll. They were the big-wave aces of the era and had spent the previous two decades pushing boundaries at Hawaii’s outer reefs. And it’s at this point in the story that surf history was made.

As the swell pulsed in the afternoon, Noll paddled into what is believed to be a 35-foot wave—the biggest ever ridden at the time. Noll didn’t successfully ride the wave, getting a beating so severe that shortly thereafter, he walked away from big-wave surfing altogether and pursued a life as a fisherman in Crescent City, California.

“Greg Noll’s monster drop-to-annihilation wave at Makaha on December 4, 1969 was the defining wave of surfing’s defining big-wave swell,” Matt Warshaw wrote in his Encyclopedia of Surfing.

“We eventually made it over to Makaha, but Greg Noll had already come in from his historic ride, and nobody was out,” Brewer woefully recalled.

A few days later, the swell marched across the Pacific and smashed into California. And with Santa Ana offshore winds blowing, the coast lit up from Mexico to Canada.

Oceanographer and 1966 Duke Kahanamoku Invitational winner Ricky Grigg rode 18-footers at San Diego’s La Jolla Cove; at Rincon in Santa Barbara, board shaper Al Merrick, U.S. champion David Nuuhiwa, and world contest finalist Reno Abellira all rode triple-overhead point surf.

Conditions that day, Merrick later recalled, were almost supernaturally aligned: “Like perfect six-foot Rincon, except it was 20-foot,” Warshaw recalled.

As I write this, a week ahead of Christmas, I’m eyeing the Surfline forecast. There’s a three- to five-foot southwest swell lurking on the horizon. It won’t be anything like the Swell of ’69, but after the year we’ve had, head-high and glassy sounds like a Christmas gift I can get behind.

Jake Howard is local surfer and freelance writer who lives in San Clemente. A former editor at Surfer Magazine, The Surfer’s Journal and ESPN, today he writes for a number of publications, including the San Clemente Times, Dana Point Times, Surfline and the World Surf League. He also works with philanthropic organizations such as the Surfing Heritage and Culture Center and the Positive Vibe Warriors Foundation.